It’s impossible to travel to Indonesia without encountering batik. This intricately patterned fabric—characterized by lively geometric and organic motifs traditionally created using a wax-resist dyeing technique—is so intrinsic to the Southeast Asian nation’s culture that it’s used to celebrate births, weddings, and deaths, its designs and colors carrying deep symbolic meaning.

Although Indonesia is the longtime spiritual home of batik fabric and the place where it reached the peak of sophistication, the technique was practiced as far back as the 4th century BCE in ancient Egypt, when cloth bearing patterns etched in wax relief was used to wrap mummies. Batik likely made its way to Indonesia via India or Sri Lanka, and early examples have also been found in such disparate places as Nara, Japan, southern China, and Nigeria.

The Western world first learned about batik in 1817, when Sir Stamford Raffles, a British colonial official and governor of the Dutch East Indies, published The History of Java, creating something of a mania for the fabric. In the 1890s, a group of young artists in Amsterdam introduced a line of batik textiles and furnishings that found an enthusiastic audience, and by the mid-1920s, the fabric reached the height of its popularity, with European and American artists and craftspeople producing it en masse. Interest in the art was revived in the 1960s, when Westerners began traveling to Bali on the hippie trail.

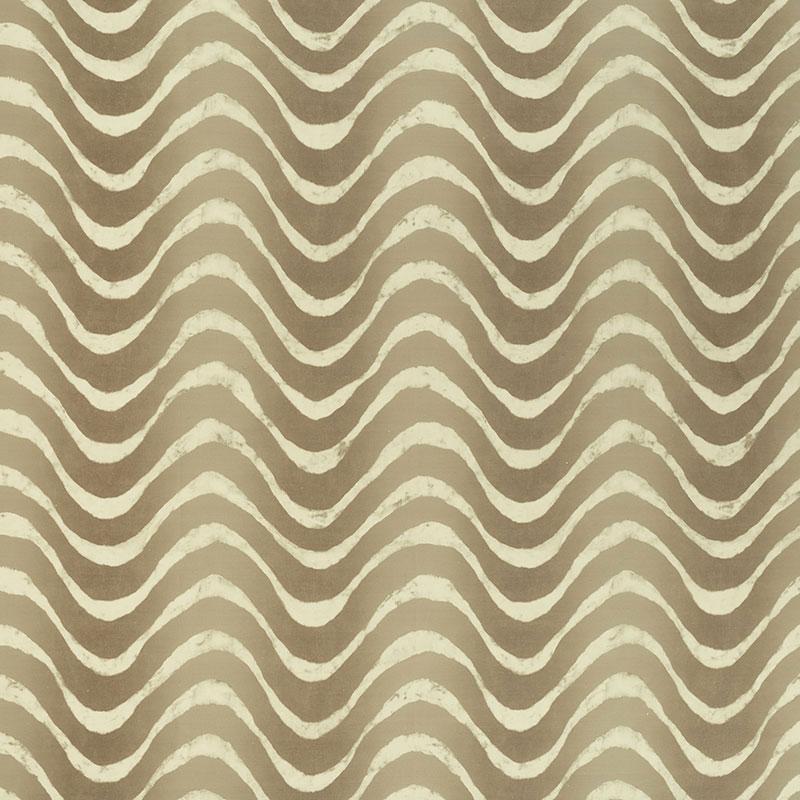

London-based designer Rita Konig inherited a love of batiks from her mother, renowned British decorator Nina Campbell. She dreamed up her own modern version, the bias-stripe print Ronnie, as part of her first-ever fabric collection, a collaboration with Schumacher.

Francesco LagneseIn Indonesian Patterns, Tradition Runs Deep

Highly symbolic, Indonesian batiks are infused with meaning. On Bali, vivid images of fish and shrimp make up Ulamsari Mas patterns, which represent the abundance of the surrounding seas and are linked to prosperity. In Solo, Java’s ancient cultural capital, Truntum patterns comprise a geometric trellis of stars representing an old tale about rekindled love (not surprisingly, they’re exceedingly popular for weddings). And in central Java, the sacred Parang pattern is a symbol of security that can be traced back to a 16th-century folktale about a Javanese prince. Then there are the Buketans—derived from the Dutch word boeket, or bouquet—the patterns perhaps most familiar to Westerners. Created by Dutch designer Eliza van Zuylen in the 1890s, these fabrics merged Javanese motifs with Art Nouveau designs in the form of flower bouquets.

Inspired by 1970s and ’80s batiks, Ronnie has the look of a traditional wax-resist print, with a swirling linear design and an earthy palette.

Francesco LagneseDrawing with Wax: The Making of Batik

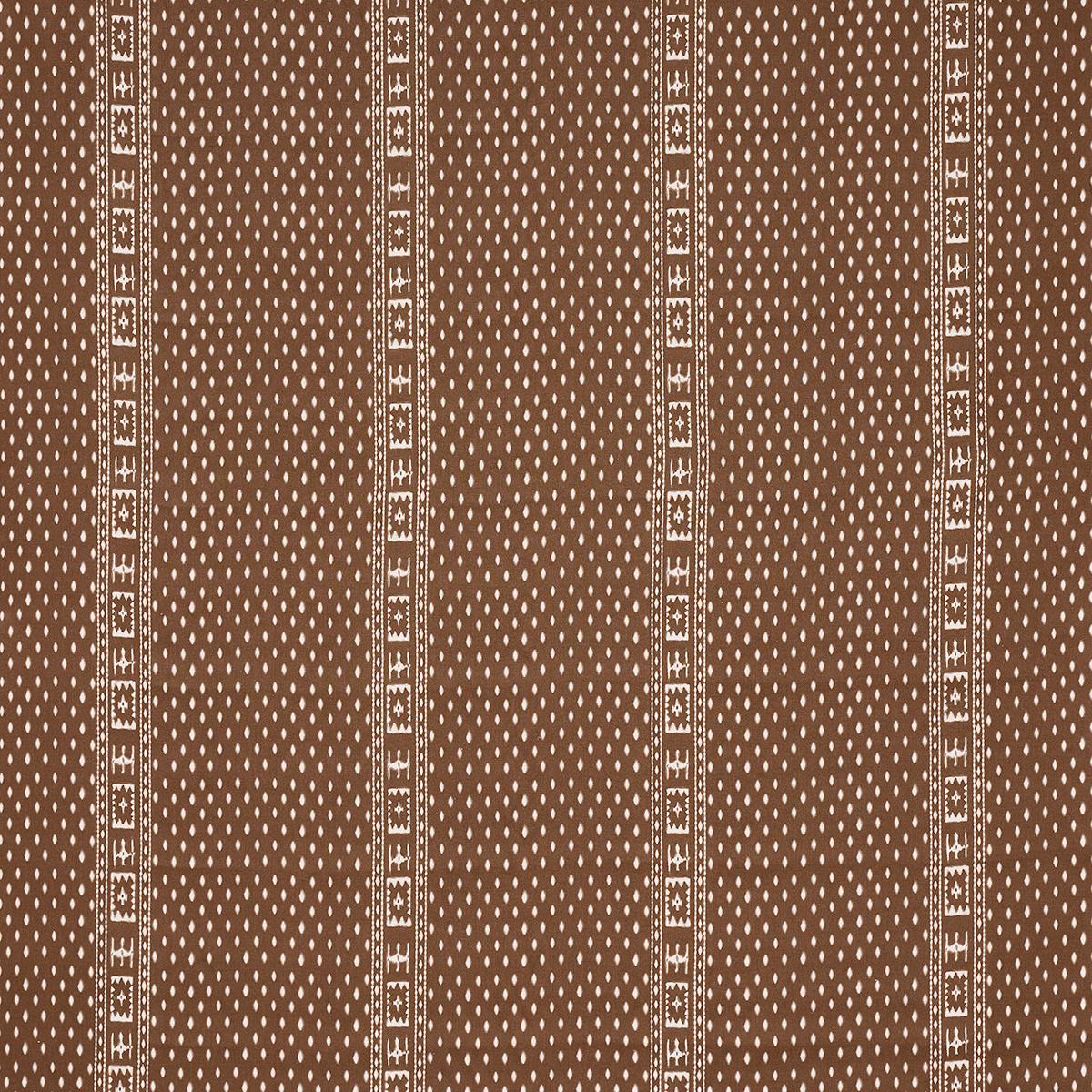

The word batik—a Dutch version of the Javanese bathikan, which means “drawing,” “writing,” or “mark-making”—can refer either to the fabric itself or to the age-old wax-resist process used to produce it. Traditionally created on a plain cotton or silk ground, true Indonesian batiks made with this technique are incredibly labor intensive. First, fine lines and dots of melted wax are applied by hand using a small thin-spouted brass vessel called a canting. When the fabric is dyed, the waxed portions remain uncolored, revealing an intricate pattern. The wax is then scraped away or removed with boiling water, and the process is repeated with as many colors as desired.

In the late 1890s, in an attempt to increase production and satisfy the demand that came with the fabric’s popularity in the West, a new technique employing copper stamps was introduced. Much like wood-block prints, these stamps could cover larger areas of cloth with wax. Simultaneously, synthetic dyes were also put to use, providing much brighter colors than those achieved via traditional vegetable dyes.

The same basics are used to create batiks in other regions, although the patterns differ stylistically. In West Africa, for example, where batik-style fabrics referred to as African wax prints have been popular since the form was introduced by Dutch and English merchants in the 19th century, artists have made the technique their own with much larger motifs, more graphic lines, and brighter colors.

You can get the look with Schumacher’s Moka fabric, a true batik made with a hand-stamped wax-resist pattern. Other batik-inspired prints like Kalahari and Rita Konig’s Ronnie deliver the feeling of a handmade textile and pay tribute to the rich history of this storied craft.