Ikat is a patterned fabric made using a unique and laborious decorative technique. Called kasuri in Japan, asb in the Arab world, matmee in Laos and atlas in Uzbekistan, it has mystified historians, beguiled legendary designer Oscar de la Renta and gobbled up the fortunes of entire families who once bought reams of it to display their wealth. Derived from the Malay word mengikat—to tie—ikat is in essence a breathtakingly gorgeous, mind-bendingly complicated form of tie-dyeing.

How Are Ikats Made?

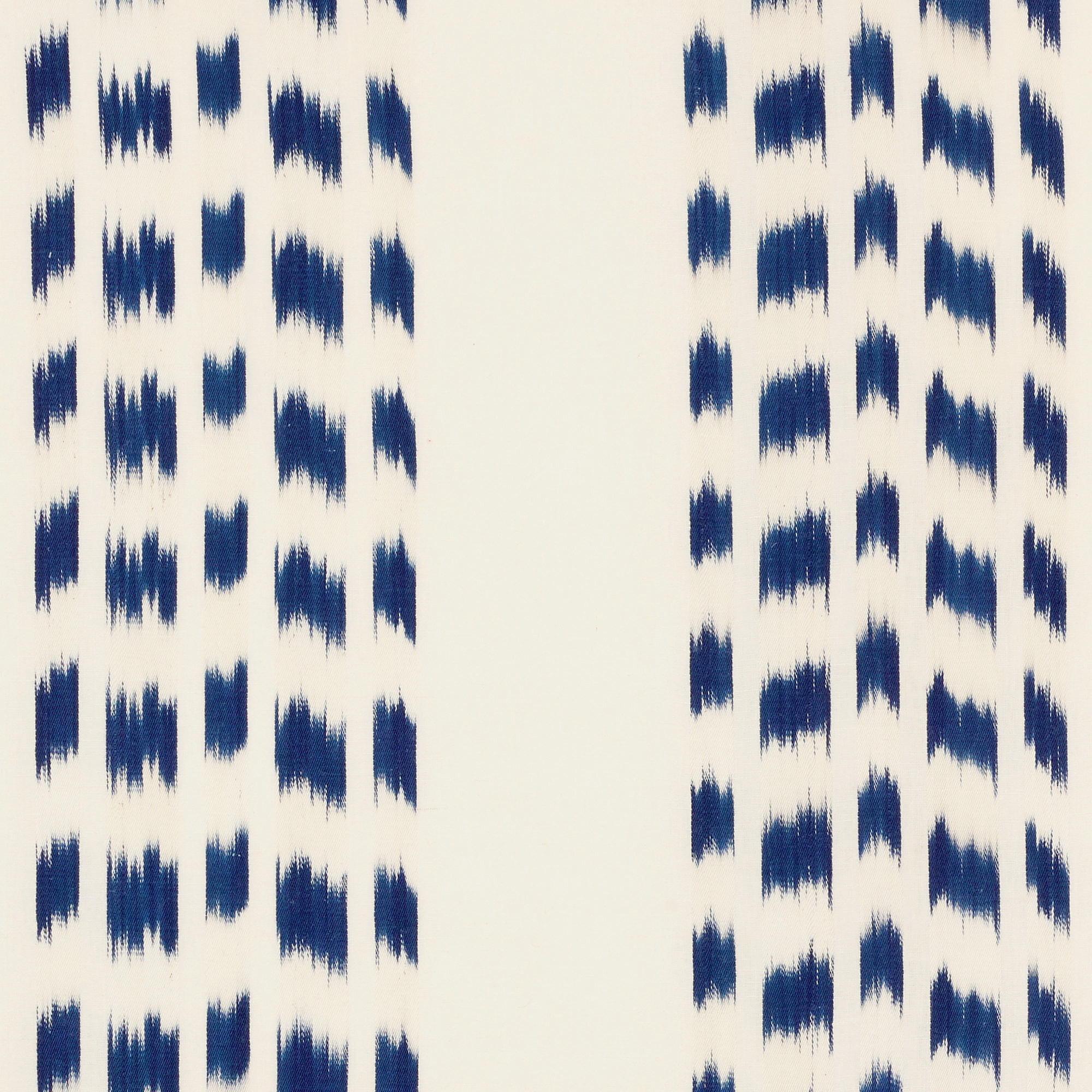

To produce warp ikats, such as Schumacher’s Santa Barbara Ikat by Mark D. Sikes, artisans create patterns in the warp yarns with a resist-dyeing process prior to weaving them into the finished fabric.

Ikat refers to both the fabric and the technique used to create it, which involves resist-dyeing yarns before they are woven. First, individual threads are tightly bound, wrapped with string to create the desired pattern and dyed. To create multicolored fabrics, this process is repeated with each dye color. The yarns are then wound onto spools in a predetermined order that must be vigilantly maintained throughout the entire weaving process, or else the design will be spoiled. Even with the most meticulously planned designs, it’s impossible to get the patterns to land precisely. That’s what creates the magic—the stunning visual effects, the vibrating, mystically blurred edges—of ikats.

Ikats can be broken down into three main types:

- Warp ikats are made by dyeing just the warp yarns, which are attached to the loom and remain stationary throughout the weaving process. This is the simplest ikat technique, and it generally results in crisper, less feathery designs.

- Weft ikats are made by dyeing just the weft yarns, which are then woven through the unpatterned warp yarns. Since the weft yarns are not stationary, it’s more difficult to achieve precise patterns—but therein lies the beauty.

- Double ikats are made by dyeing both the warp and weft yarns. These designs are incredibly difficult to achieve, and planning out the patterns is a puzzle that only master weavers can solve. Given the skill and difficulty involved, double ikats are the rarest and most expensive.

Where Did Ikats Come From?

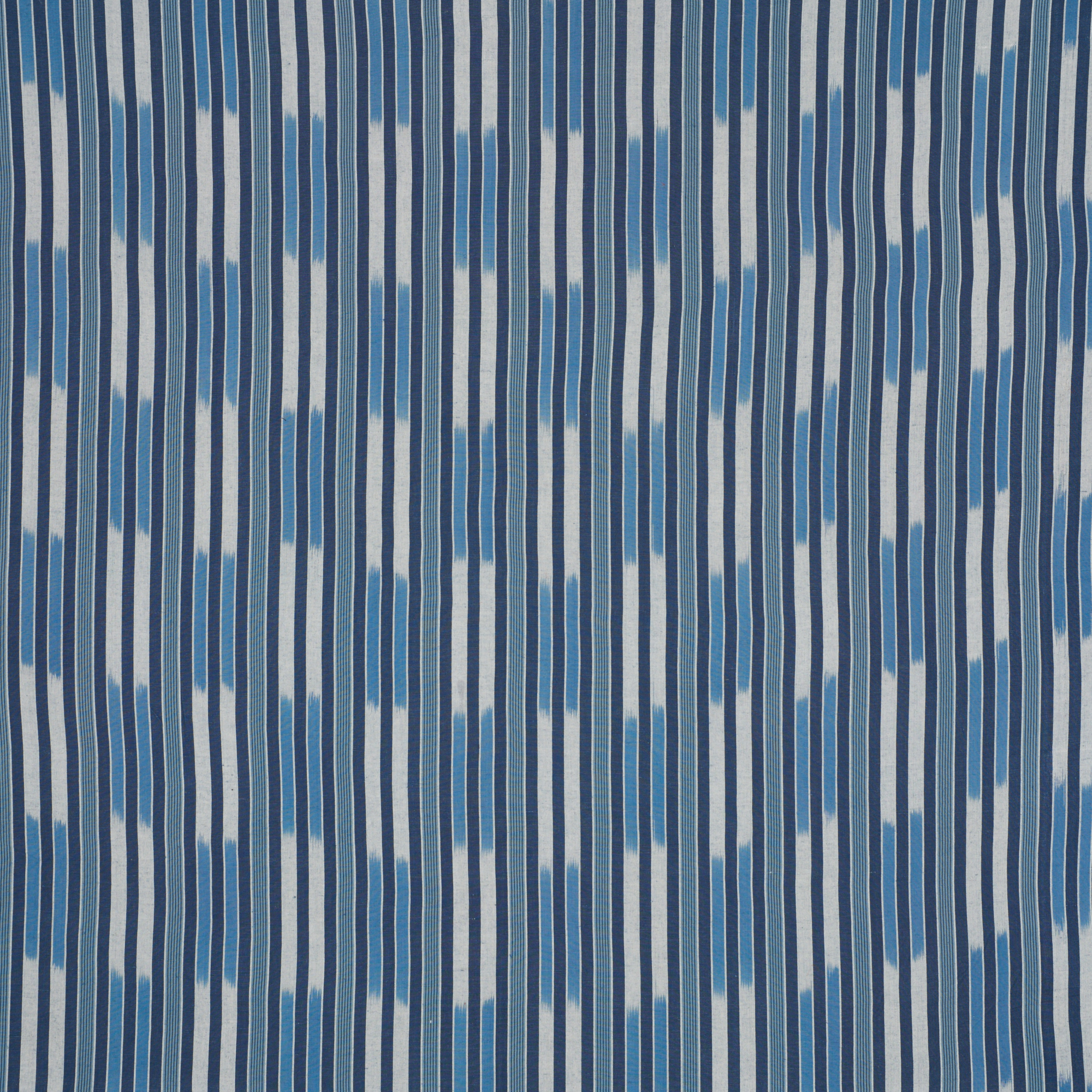

Balancing crisp stripes with just the right dash of movement and variation, Santa Barbara Ikat by Mark D. Sikes works beautifully in laid-back rooms and more-formal spaces alike.

Amy NeunsingerAh, good question. It’s one that has stymied historians ever since they began studying textiles. While most weaving techniques can be traced back to a single region, historians have never unraveled the birthplace of ikat. That’s because it seems likely that these textiles sprung up independently in different regions and cultures that never had contact. The earliest surviving ikats were found in Japan, and made in China in the 7th or 8th century. But pre-Incan examples dating to the 8th century have also been discovered in Peru, and evidence of the technique can be found in West Africa, India, the Middle East, Iran, Syria—the list goes on. What is known is that the Dutch first introduced the technique to Europe in the early 1900s from Indonesia, which has one of the world’s richest ikat heritages.

Ikat’s Haute Couture Connection

A large-scale pattern in an array of brilliant hues, Terence Ikat by Johnson Hartig captures the Libertine designer’s signature offbeat style in a time-honored warp-print technique.

Paul CostelloIn the 19th century, Uzbekistan was a hotbed of ikat weaving, turning out flowing robes of magnificently colored silk with psychedelic geometric patterns. These masterpieces only came to the attention of Western collectors after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. After his first glimpse, fashion designer Oscar de la Renta became completely captivated by the fabrics, visiting Uzbekistan and commissioning local weavers to create endless lengths of the fabric. In 1997, his haute couture collection for Balmain was nothing but brilliant ikats, and he continued to incorporate the fabric in his collections until his death in 2014.

What’s the State of These Fabrics Today?

Clockwise from top left: Schumacher’s Asaka Ikat in Violet, Samarkand Ikat II in Ruby and Bukhara Ikat in Fuchsia.

After de la Renta put them in the spotlight, ikats exploded in both fashion and interiors. Those made the traditional way immediately convey a haute bohemian style embraced by designers like Rifat Özbek, Charlotte Moss and the late Robert Kime. Yet as ikats have grown in popularity, budget-friendly printed alternatives have made the motifs more accessible—and the best versions are calibrated to capture the subtle striations of the real thing. Printed ikat motifs can also be translated to wallpaper, allowing designers to wrap an entire room in these coveted, richly dimensional patterns.

Of course, it’s hard to top the beauty of a true ikat. To spot the genuine article, just flip the fabric over: Warp, weft, and double ikats are always patterned on both sides. Consider it a mark of historic beauty.